This is not the hat that will decide whether you’re assigned to Hufflepuff, Ravenclaw, Slytherin or Gryffindor.

This is not the hat that will decide whether you’re assigned to Hufflepuff, Ravenclaw, Slytherin or Gryffindor.

It is much more contentious than that.

This is the hat you put on when you decide how you are going to arrange your collection – alphabet or genre – and, currently, one of the hottest topics on discussion lists I belong to. Any question about changing the arrangement from the more traditional author-alphabet base to one based on the perceived genre elicits hot and fierce debate as proponents and opponents put their perspective.

The common arguments are…

- students find it easier to find the sort of book they want in a collection sorted by genre

- collections arranged alphabetically keep all the titles by the same author together

- if students only select from a preferred genre their reading choices are narrowed

- students prefer the bookshop look of the library because it is more modern

- if students learn the traditional method of the first three letters of the author’s name they will be able to transfer those skills to locating titles other libraries

- one title might fit a number of genres so how will its placement be determined

In my opinion the decision is easy and is based on the belief that

The collection exists to meet the needs, interests and abilities of its users and to meet those needs it must be accessible

Therefore, as the teacher librarian we must know our readers and what their needs are. What might be appropriate for the users in one school library might not work for the users in the school in the neighbouring suburb because each school population is unique.

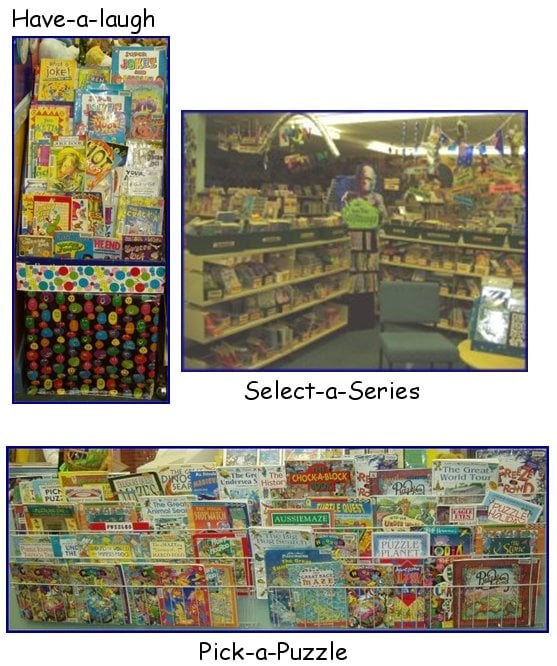

Even if we currently classify fiction in alphabetical order by using the first three letters of the author’s name, we have modified Dewey’s original arrangement (because he assigned specific numbers between 800-899 to literature) so that users can find what they want more easily. Then, to make it even easier, we might shelve all the episodes of a particular series together or pull all the fairytales into one smaller collection. We separate based on format – picture book, novel, information book, DVD – and intended target audience such as junior fiction and senior fiction. In the non fiction collection all the biographies might be shelved in one spot rather than in their specific subject of expertise as Dewey mandates or the puzzle books might have their own space so they are easier to find and shelve. Already we are ‘tampering’ with tradition and accepted practice because we want to make the resources more accessible to those who are using them.

So why is the decision to arrange the collection according to genre so controversial?

Firstly, the term ‘genre’ must be clarified because there is a tendency to interchange the word ‘genre’ with ‘text-type’ leading to confusion between format, purpose and content. Genre itself just means ‘a type or a category’ and it is generally applied to literature, music and the arts. Within literature it refers to prose, poetry, drama or non fiction, each with its own style, structure, subject matter, and the use of figurative language.

However, in education realms it is also often used to describe the author’s purpose – to persuade, inform, entertain or reflect. And these categories have been broken up even further …

Rose (2006) cited in Derewianka, 2015

However, in terms of the arrangement of the collection we are referring to another ‘definition’ of genre – those divisions of fiction based on theme, plot, characters and setting. It refers to categories such as adventure, romance, fantasy, historical and contemporary fiction although there is a much larger list of possibilities and the sort of arrangement that is proposed has become known as ‘genrefying’.

If we return to the the underlying premise that the collection exists to meet the needs, interests and abilities of its users, then it stands to reason that as a priority we need to identify what those are, particularly in relation to their preferred way of selecting their reading resources for leisure and pleasure. We need to ask questions to identify if genre is their first and primary criterion for selecting a new read and the sorts of stories they like to read. (Thinking Reading provides a starting point to survey your readers on a number of issues to enable informed collection development.) My experience and research has shown that, generally, primary age students do NOT use genre as their search criteria. While they may like mystery or adventure or whatever books, their choices are made based on

- peer or teacher recommendation

- series

- popular movie, television or game tie-in

- author

- cover

- blurb

- serendipity

But my experience is not your experience and all sorts of factors come into play such as

- the age and maturity of the students

- their proficiency with English (or the predominant language of your collection)

- the focus of the curriculum

- their access to reading materials beyond the school

- their understanding of the concept of ‘genre’

So it is essential that you delve into the reading habits of those who will be reading to understand what will suit them best.

Should you discover that a collection organised by genre is what is best for your clients, then there are still a number of other questions that need to be asked and answered by the stakeholders before making such a significant change because not only is it a huge job absorbing human, financial and time resources it must also be sustained and sustainable. Those questions include…

- Why is the change being considered?

- Is this a sound reason for change?

- Is the change based on identified user needs or preferences?

- Why is what is currently in place not working? What is the evidence that it is not? How can it be changed or modified to work rather than introducing a non-standard ‘fix’?

- Is the solution based on sound pedagogical reasons whose efficacy can be measured?

- How do the proposals fit mandated curriculum requirements?

- Can the proposed change be defended based on user need, sound pedagogy, curriculum requirements AND established best practice?

- What reliable evidence (apart from circulation figures) exists to support the changes and demonstrates increased engagement and improvement to student learning outcomes?

- Will the proposed changes lead to students being more independent, effective and efficient users of the library’s resources?

- Will the changes impact on the students understanding of how other libraries are arranged and their ability to work independently within those?

- Have students had input into the proposal?

- How will the change support the Students’ Bill of Rights?

- Will the change marginalise or discriminate against any users such as identifying their below-average reading level or sexual preferences?

- Will the change broaden or narrow the students access to choices and resources?

- Is it based on school-library best practice? Are there successful models (measured through action research and benchmarks and published in reliable authoritative literature) that demonstrate that this is a sustainable, effective and efficient model to emulate?

- Will the change make it easier to achieve your mission statement and your vision statement?

- How do the changes fit within your library policy, which, presumably, has been ratified by the school’s executive and council? Will the change in procedure require a change in policy?

- Who is responsible for developing the parameters of the change and documenting the new procedures to ensure consistency across time and personnel?

- If a change is made, what S.M.A.R.T. goals will be set to measure its impact?

- When will the impact of the change be assessed and what evidence of success or otherwise will be acceptable to the stakeholders?

- Who will do the measuring and ensure that the conclusion is independent and unbiased?

- If those goals show no change or a decline, will the library be willing to reverse the process? Will this be a practical proposition?

- How will the proposed change impact on the role and workload of the teacher librarian?

- How will the proposed change impact on the role and workload of other library staff?

- If the change changes the traditional library arrangement, how is consistency across time guaranteed if personnel change because decisions are subjective?

- Who is responsible for developing and maintaining the criteria for placement and the Procedures Manual to ensure consistency?

- Is the change worth the time that is invested in re-classifying every title and the money invested in new labels, staff wages etc?

- Could that time and money be better spent?

- Would better signage, including more shelf dividers, address the problem?

- What role can displays play in highlighting different and unfamiliar resources to broaden access and choices?

Documenting the answers to these questions (and others that will probably arise along the way) not only demonstrates your professionalism and the depth of consideration that has gone into the decision but also provides you with a solid foundation of evidence on which to defend that decision should it be challenged.

Having invested the resources in making the change, a new range of issues arises particularly in relation to how you teach staff and students how to use the new arrangement effectively, efficiently and independently.

- Do they understand the concept of ‘genre’ in this context and the sorts of criteria that distinguish one from another?

- How will you teach these? Will teaching the characteristics of each genre become your predominant teaching focus to the exclusion of other curriculum priorities such as information literacy?

- What will be the genres that you choose and how will these be decided?

- Are the genre labels appropriate for the users? For example ‘romance’ might not appeal in an all-boys school but ‘relationships’ could encompass the concept.

- How will the genres themselves be arranged – alphabetical order, popularity, size of the particular collection?

- Will individual titles within each genre then be organised in alphabetical order of author or is there another way?

- How will you deal with titles that span two or more genres?

- How will the genre of each title be identified both on the book and in the catalog?

The arrangement of the resources in your library has to be based on so much more than the outcomes a retailer might be wanting to achieve. The school library is not a bookshop on steroids and the sorting hat must be one that is put on with extreme care and consideration. Of all the hats we wear, this is definitely not a one-size-fits-all.