Being an “independent reader” is much more than the mastery of the mechanics – it involves having an emotional attachment that makes the experience a part of who we are as a person, embracing the affective domain as well as the cognitive and the physical.

Being an “independent reader” is much more than the mastery of the mechanics – it involves having an emotional attachment that makes the experience a part of who we are as a person, embracing the affective domain as well as the cognitive and the physical.

Being an independent reader means developing a lifelong habit that continues because we want to read and not because we are required to or have to. It means that we read even when daily support such as dedicated in-class reading time such as the DEAR and USSR programs are no longer available.

In her book Reading in the Wild , a professional text that has had the greatest impact on my beliefs and actions of any I’ve read for a very long time, Donalyn Miller identifies five key characteristics of an independent reader…

- They make time to read and dedicate part of each day to doing so.

- They have the confidence, experience and skills to self-select reading materials

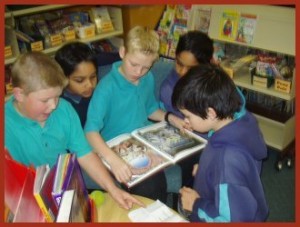

- They share their books and reading experiences with other readers

- They have a reading plan– they know what they will read next.

- They show and share preferences for particular authors, genres and topics.

While Miller’s book focuses on her experiences with her classes who have access to an extensive classroom library, the purpose of this blog post is to examine how we, as teacher librarians, can put in place supports that will enable students to move along the spectrum of reading mastery to complete independence.

Read the research

Apart from the research about the value of being able to read well which Miller cites in her books, there are also some important studies being undertaken that we should know about, particularly if there are moves afoot to abandon print resources in the library or discourage the reading of fiction. These are the key papers that are impacting on current collection development that I believe we should all know about.

All should be on our professional reading lists.

In her 2014 paper, Children and Reading : Literature Review Dr Dianne Dickenson provides a snapshot of what 5-14 year-olds in Australia are thinking and doing in relation to reading right now. While it states that “there is a vibrant culture of reading and writing in Australia right now” it also identifies Australian Bureau of Statistics research which shows that there has been “a significant fall in children’s reading for pleasure … from 2006-2012”. Libraries, although not school libraries specifically, are identified as an important source of reading materials for children but it also acknowledges that there is a new concept of what reading is emerging – that it no longer is confined to traditional print resources – and thus new research needs to be undertaken with this included. It also identifies other gaps in the research which might offer food for thought for those with a research-oriented brain.

As well as formal research there are also some professional texts that should be a core element of your personal professional collection.

The Book Whisperer |

Reading in the Wild |

Reading Magic |

The Read-Aloud Handbook |

The Power of Reading |

Igniting a Passion for Reading |

|

Readicide |

|

Think like a reader

When Miller talked to her students about reading, she discovered that many of them viewed reading as a school-based activity, something done to achieve something else, please someone else or an obligation done for points, a grade, or a positive comment on a report. Others, including me, have found that students don’t see themselves as readers – that’s something that adults and others can do. Seldom do they classify themselves as readers because in their view, readers read fluently and perfectly without errors – something they don’t yet do. They also see “real reading” as something done with a traditional print-based object even though they might be succeeding very well within a different medium. So we need to help them view themselves and reading in a different light.

Firstly, we need to broaden our concept of what reading is. Is it confined to traditional print materials or does it include how children relate to the diversity of digital media? If we are observing their reading behaviour, either formally or informally, what is it that we are looking for? Qualitative measures like enjoyment and engagement, sharing and suggesting, taking risks to try new authors, topics and genres? Or quantitative measures like progress along an arbitrary achievement line, comprehension scores and other standardised progress measures?

Secondly, we need to think about the language we use when we talk to them about their reading. Is their concept of “reading” the same as ours’? As discussed in the learner’s hat one of the drivers of learning is that there is an expectation that the learner will succeed, so we need to shape our comments, questions, suggestions and tasks so the students believes they can achieve this exulted title of “reader”.

Thirdly, we need to get them to focus on their reading – what they read, what they like, how often they read, where they read … all sorts of questions that help them understand that they can and do read beyond the scope of a classroom-based task and a print-based object. In collaboration with the classroom teacher we can get students to complete a personal survey thinking_reading to focus on their habits which will give both student and teacher an insight into their preferences.

Then, we can get them to track their reading so they have a visible record of it. Very young students might have something like a themed-chart with ten spaces and a star is placed in each for each book read while older readers could have personal reading journals which contain reading logs, responses, to-read plans and so forth. Services like Goodreads and Shelfari offer an online option for this but you might also consider Biblionasium or A Book and a Hug which have been designed for young readers. However, while we want the students to track their reading so they can identify their preferences, plan their future reading – both characteristics of independent readers identified by Miller – and prove to themselves they are indeed readers, the paperwork should not become more important than the reading. While individuals might set themselves personal challenges to accomplish, the reading record should never be a competitive document. Tracking their reading also enables them to make recommendations for their peers, both positive and negative, and this contributes significantly to their perceptions of themselves as readers. Many of these crowd-sourcing sites also offer suggestions for new reading based on the student’s entries, so that helps develop a reading plan for the future.

Time to read

No one will deny that reading proficiency is dependent on practice and that, of course, requires time. But students, like adults often find it difficult to find this time both at school or at home. However, if students see that the significant people in their lives read and make the time to do so because they value reading they want to be be a part of that reading community, belong to that “in-group”, sharing experiences and forging bonds that help them define themselves as readers.

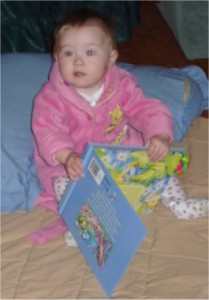

Students often see reading as an all-or-nothing event – something that is done in blocks of 30 minutes or so, 30 minutes that they don’t see themselves as having in their hectic school and after-school lives. Miller suggests the solution to this is to get students to read “on the edge” although “in the gaps” might create a stronger visual image, but they need to learn how to identify those gaps, such as waiting for the bus or an appointment or during a sister’s soccer practice. As TLs, we can lead a lesson where we help our students identify those gaps and turn them into opportunities. Teach parents to read in the gaps too – encourage them to have a book in their bag that they can read aloud to their child, such as I did yesterday when I had the chance to look after Miss 2 while Miss 7 was busy so we sat and read together, much to the delight of the other patients who enjoyed her version of The Gruffalo’s Child and didn’t have a bored 2 year-old disturbing them. It teaches the young child so much about reading…

Miller suggests having them keep a reading itinerary for a week, identifying when they read, where they read and for how long. This not only helps them look for those opportunities but also helps them understand where they are most often and most comfortable reading. This can lead to individual discussions that help the student gain insight into their reading habits, and that it can be done anywhere, anytime even just for a few minutes.

As well as helping the students make time to read, look for opportunities to promote reading within the community and read aloud to students. Consider…

For a comprehensive list of events as well as opportunities to highlight reading in the library click here. Add to the document if you can.

A place to read

As the TL we should be able to set up areas that are conducive to personal reading within the library and which students can use during breaks. There should be spots for individuals who like to curl up in out-of-the-way spots and be alone in the world of their book as well as places where they can share what they’re reading with their friends. Have a special story-teller’s chair where they can role-play being the TL or their teacher -anywhere that invites them to spend a few minutes just reading.

Couches, beanbags … comfortable seating entices readers |

I purchased bean bags for my library and was fortunate enough to have a couple of couches donated. Students love to curl up in these and read to themselves or to the teddies that were always there as a friend.

As well as making places and spaces in the library, look for other areas around the school where students have to wait and possibilities for reading are created. Ask parents for donations of comfortable chairs and leave a pile of books that can be taken and returned or not.

A reason to read

A writer can’t help but divide all the world he knows between readers and nonreaders.

I can only reach for the readers, and through them, the future. I conclude then, in the voice of a young reader,

I read because one life isn’t enough, and in the pages of a book I can be anybody;

I read because the words that build the story become mine, to build my life;

I read not for happy endings but for new beginnings; I’m just beginning myself, and I wouldn’t mind a map;

I read because I have friends who don’t, and young though they are, they’re beginning to run out of material;

I read because every journey begins at the library, and it’s time for me to start packing;

I read because one of these days I’m going to get out of this town, and I’m going to go everywhere and meet everybody, and I want to be ready.

Peck, R. (1991) Anonymously Yours. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Messner

Encourage students to read by setting up interactive displays that require them to read. Two of the most popular I created were based on setting up Graeme Base’s The Eleventh Hour as a whodunnit with a clue released each day, and a series of challenges based on Emily Rodda’s Deltora Quest which meant the students had to read the books to complete the tasks and earn another stone for their belt. Look for books that lend themselves to such treatments and beg, borrow or buy enough copies for the participants.

| CSI was very popular on television at the time so it inspired an interactive display based on The Eleventh Hour by Graeme Base. The library was the place to be at lunchtime, and reading was the thing to do. even the most reluctant readers in this cohort wanted to be part of the in-crowd. |

|

|

|

|

|

Set challenges that can be completed by the students as a reading community. HarperCollins have a poster of an A-Z of literary characters which, because it has a strong US orientation, could be a model for creating an A-Z of Australian literary characters. Or set personal challenges such as Read-a-Rainbow in which each student selects seven genres to read over a set period time, completing an appropriately illustrated record for their reading journal.

The opportunities are endless but my rule of thumb was not to put anything on the walls that did not have a reason to read to accompany it.

Growing readers

If our students are to grow into competent, confident, independent readers we need to help them by actively promoting opportunities for them to broaden their experiences. For every TL in every school library there is an idea of how this can be achieved but here are a few…

- collaborate with the classroom-based teachers who set reading-based assignments, encouraging them to set open-ended tasks which students can meet using texts of their choice, avoiding the traditional one-size-fits-all class novel

- support what is being taught in the classrooms by creating displays of resources, particularly fiction, which are aligned to the topic. Teachers may well clear the shelves of non fiction resources but often fiction focusing on a particlar time, place, event or topic will offer extra insight

- read aloud to students of all ages, not just those unable yet to read for themselves, and suggest appropriate read-alouds to your classroom-based colleagues. Read-alouds

- build a sense of community through shared experiences and memories, as well as sharing those books that are valued by the community at large

- introduce students to titles, authors, genres and topics that they might not discover for themselves or which they avoid or which are beyond their independent reading level at the time

- they make popular texts accessible to those who, for whatever reason, are not yet able to read them for themselves enabling them to share in the conversations about current fads

- support developing readers through discussion of unfamiliar vocabulary, concepts and contexts which enhance comprehension, as well as enabling them to hear fluent reading and the nuances of our spoken language

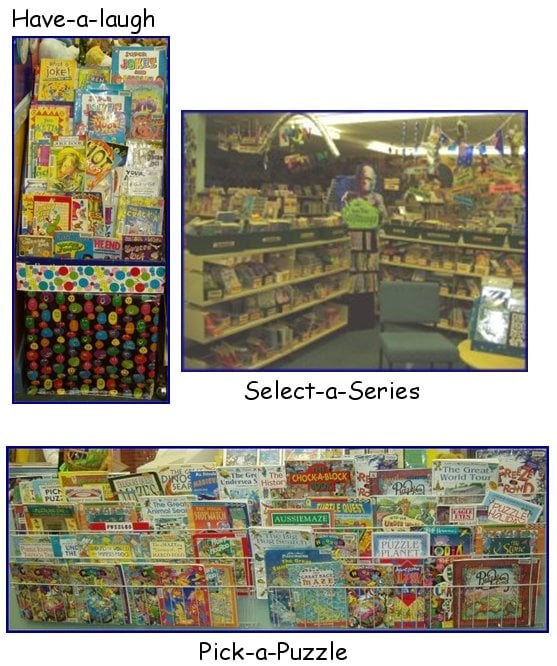

- plan specific activities within your teaching programs which highlight books, authors, genres, formats and series so that students have a feeling of familiarity when they recognise them on the shelves

- build anticipation for new releases through promotions and competitions, ensuring that allocations are fair and that there is the opportunity to reserve titles

- recognise those readers who might have a passion for a particular author, genre, topic or series and direct inquiries about them to those students. This is particularly effective for those who may not be the leading lights in a class and whose self-esteem needs a boost.

- talk to reluctant readers about the things they are interested in, not just what they like to read about, and direct them to titles – fiction and non fiction – so they learn that the library has stuff for them too. Look to cater for that ‘long tail’ who have yet to learn that reading and libraries are relevant for them

- create and promote displays of authors, illustrators or topics that you know appeal to a particular group but which they haven’t discovered yet

- create and promote displays of themes such as sustainability, values, international stories to bring unfamiliar resources to the fore

- offer an engaging display of genres and have students commit to reading a selection of them including some that are unfamiliar but allow them the ownership of their choices

- troll winners of awards from home and overseas, add them to your collection and promote them

- if award winners drive your literature program but you need those titles for teaching, look for other titles by the authors and offer these

- offer reading materials in a variety of formats so they appeal to a wider range of readers

- challenge students to read the winners, honour books or shortlists for a particular award for the year they were born

- capitalise on special days and develop activities that promote these such as speed-dating with books on Valentine’s Day

- exploit interest in movies, television shows, online games and apps by providing the books on which they are based

- promote author studies and organise author visits

- publicise and promote target resources through blogs, booktalks, book trailers, school notices and newsletters – any opportunity which presents itself

- if your school requires readers to keep a reading journal then 10 authentic ways to hold students accountable for home reading offers suggestions that might refresh old practices. Biblionasium is a great place for under-13s to reflect and share.

Here are some more suggestions from teachers in the UK … How to encourage students to read for pleasure: teachers share their top tips.

Growing readers is one of the most important parts of our role – it requires both our teacher and librarian hats because we need to know how students learn to read and then how to develop a collection which meets their needs.

Use this publication Get Everyone Reading from the UK School Library Association for ideas that promote reading across both the staff and student body.

Encouraging self-selection

Neil Gaiman says

Read. Read anything. Read the things they say are good for you, and the things they claim are junk. You’ll find what you need to find. Just read.

It is our role as teacher librarians to enable our students to do just that. Confident self-selection is one of the hallmarks of an independent reader and there is a range of research which demonstrates how choosing their own texts enhances engagement and promotes reading motivation and interest. Allowing students to take responsibility for selecting their reading materials

- boosts their confidence in their ability to make decisions

- provides a sense of ownership of the choices and thus a greater motivation to read them

- increases their knowledge about authors, topics, series, genres and formats

- helps them become more discerning about their likes and dislikes

- teaches them that it is OK not to finish something that doesn’t live up to expectations

- enables them to match their choices to their particular life circumstances at the time – sometimes a light read is appropriate, sometimes something more challenging

As teacher librarians and student advocates we must resist any demands to organise the library’s collection based on arbitrarily imposed reading levels, grade levels, points systems or any other device or system which limits the students’ choices. We need to refuse to identify books in any way that might marginalise readers or discriminate against them whether that be ability-based, cultural, religious, or sexual orientations, or any other criterion that might result in a student refusing to read at all. We need to know the research so our refusal can be defended on pedagogical grounds and be willing to require those wanting change to answer those questions identified in the information specialist’s hat.

Self-selection needs support and I’ve already shared some suggestions on how to do that as you grow readers. However, Miller also identifies having a reading plan as a critical characteristic of being an independent reader and in her case her students have preview stacks of books they might like drawn from her extensive classroom library. A more practical situation in the school library situation is to encourage students to create to-read lists, either print-based in their reading journals such as growing_reading or using an online service such as Goodreads. or Biblionasium for the under-13s. Recording recommendations not only offers a plan for the future but it jogs the memory and allows the reader consider options that might meet the particular circumstances.

Miller also encourages her students to examine their reading, particularly the last five books they’ve read, and ask these questions to help them reflect on their selection methods and thus fine-tune them.

-

- How do you find out about books that you would like to read?

- Which sources influence you the most? Why?

- When you see a book or hear about it, how do you decide that it is a book you would or would not like to read?

- Do you ever abandon a book? Why or why not?

- Are you successful in choosing your own books to read? Why or why not?

Enabling students to self-select and ensuring they have the skills to do so is one of the most critical things we can do for our students.

Sharing reading

Sharing reading is an important indicator of an independent reader. Being able to reflect on what has been read, contribute to a discussion about it and make a judgement about its worthiness shows both competence and confidence. Providing a supportive environment which fosters a reading community in which each member sees that reading is valued and valuable and that they themselves are considered readers is a critical element.

Reading as a leisure activity needs to be as accepted as any other pursuit, and not just for those with “brains” or nerds or the socially inept. We need to surround our students with models of reading, particularly those whom they hold in high regard. So invite community members in to read to them, display posters and create displays of celebrities and sports stars reading; reach out to the classroom, home and beyond – anything that helps show that reading is cool and a mainstream activity.

Providing readers with the opportunity to share their reading means it becomes a two-way street where students know they can give and their gifts are valued. As with growing readers, there are as many ways to provide students with opportunities to share as there are TLs in libraries. But here are a few…

- Provide time for and encourage students to talk about their reading informally -often what looks like idle chit-chat is actually a reflection and and a recommendation

- Establish a quotable quotes wall. Have speech bubble templates on hand so students can record significant sentences from stories they read. Have them include the title, author and location.

- Create a book snapshots wall. Take photos of what each student in a class is reading at a particular time and create a collage. Change it regularly so all classes have a turn.

- Create a five-star display and poster where students can record the details of books they believe to have a five star rating.

- Have a Recommended Returns display where books which students highly recommend are displayed for others to borrow without having to search the shelves. Scan the covers and keep them in a folder for students to browse when they’re looking for something new.

- Invite students to create displays focusing on their favourite authors, themes or genres.

- Display a catchy caption such as The Land Before Time and have students find the resources, fiction and non fiction, that they think should be part of a display.

- Leave a legacy. Have your graduating classes decide the five titles every student should read before they leave your school and develop a display with their reasons for recommending them.

- Have students create book trailers, bookmark reviews, and blurbs to display in commonly-used places such as the bathrooms.

- Encourage students to read_and_reflect

- Explore the use of QR codes encouraging students to provide the back-end information.

- Encourage students to contribute comments to the library’s blog or other communication tools, recommending reads they have enjoyed.

- Have students track their reading using an online service such Biblionasium, Goodreads or Shelfari or using a print form such as tracking_reading

Reaching readers

We need to reach out to readers who believe reading is not for them – those who can read but choose not to and those who are still learning and are finding it a challenge – as well as those who don’t have the opportunity

- When you create a display on a topic or genre, include titles that cater for a range of abilities so students can choose the fit for them

- Invite suggestions for titles and authors from the students so you make an effort to reach out to that long tail of those who don’t come into the library

- Look for out-of-library ways to promote what you’re offering, again to reach that long tail

- Look beyond the staff and student body and consider how you can support the parents and the preschoolers so they understand the value of reading at home and can put it into practice

- Offer reading in all its guises – picture books, ebooks, novels, graphic novels, magazines, comics, instructions, captions, fiction, non fiction, in print and online – so it is seen as accessible, purposeful, valuable and valued

Putting on the reader leader’s hat is one of the most important aspects of the teacher librarian’s role. Not only does it need to be big enough to hold all the ideas and suggestions we have, it also needs to be big enough to encompass those who come under our influence.

Sadly, many of our colleagues in less-enlightened schools are asked to take responsibility for teaching a particular strand of the curriculum during their time with students, often in that time when they are covering teacher preparation and planning time. And while that can be a way to embed the information literacy skills that are an integral aspect of each strand of the Australian Curriculum, often the teaching and learning becomes a content-building exercise and tends to be limited to subjects like Science, Geography, History or Humanities and Social Sciences, or in some cases covers the broader elements of the General Capabilities and Cross-Curriculum Priorities and those Key Learning Areas become the stand that the hat is pinned on.

Sadly, many of our colleagues in less-enlightened schools are asked to take responsibility for teaching a particular strand of the curriculum during their time with students, often in that time when they are covering teacher preparation and planning time. And while that can be a way to embed the information literacy skills that are an integral aspect of each strand of the Australian Curriculum, often the teaching and learning becomes a content-building exercise and tends to be limited to subjects like Science, Geography, History or Humanities and Social Sciences, or in some cases covers the broader elements of the General Capabilities and Cross-Curriculum Priorities and those Key Learning Areas become the stand that the hat is pinned on.