A vision statement is just the beginning.

If it is to come to fruition then it needs to be teased out in and supported with a formal strategic plan which becomes the road map to the destination of your vision. Such a plan shows the pathway forward, guides decisions, helps negotiate obstacles and avoid detours, has markers and milestones which prove your progress and ensures that your steps are leading in the right direction.

It includes identifying

- purpose

- priorities

- goals

- timeframes

- performance indicators

- stakeholders

- roles and responsibilities

- financial, human, time and physical resources

- external support

- documentation

- review periods

It needs to answer these sorts of questions…

- What have we already got?

- Is this still valid, valued and valuable?

- What more do we need to have?

- What more would we like to have?

- How can we make the tasks manageable?

- What will be the roles and responsibilities of each person?

- How should the map to our destination be constructed?

- What are the priorities along the way?

- What resources are needed so we arrive at the destination safely?

- How will we know we are making progress?

- How will we know that our destination has been reached?

- Is the destination as far as we can travel or is there somewhere beyond the rainbow’s end?

Purpose

All that is done within the library, whether it is wearing your teacher’s hat or your librarian’s hat must contribute positively to the teaching and learning in the school. Whether overt or covert, it needs to support the staff and students in some way. Therefore, any changes need to be underpinned by an articulation of how they do this. Making changes based on sound pedagogical practice which is supported by evidence of its efficacy and efficiency demonstrates why we are teacher librarians with dual qualifications.

For a list of the questions which need to be considered to demonstrate that your changes are based on best practice, read The Information Specialist’s Hat

All that is done also needs to meet the needs of the library’s users, both staff and students, and these cannot be assumed. Undertaking an Information Needs Audit will provide you with insight into those services which staff and students believe to be the most useful for them. It can also serve as an advocacy tool to alert them to the range of services you provide. Clicking on information_needs_audit will take you to a pdf version.

Priorities

Not everything needs to be done at once. In fact, it cannot be as one thing is often the foundation for the next. Establishing priorities not only identifies the sequence of the plan but also provides a defence if your professional practice is challenged.

Areas of priority to be considered include

- the development of an information literate school community

- curriculum development, design and delivery

- collaborative planning and teaching

- recreational reading programs

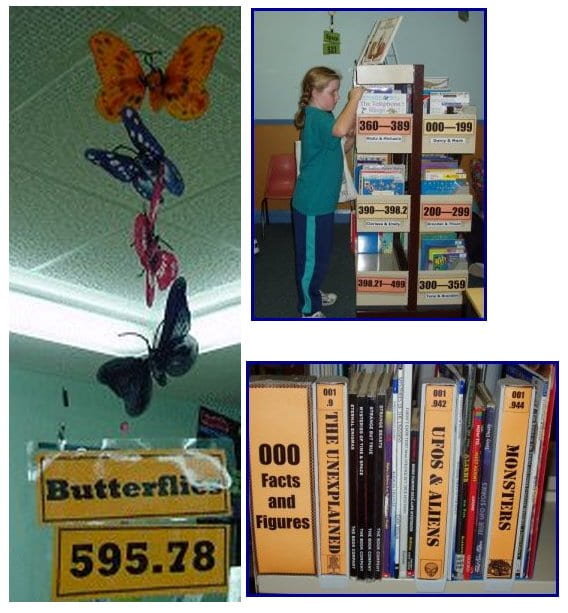

- collection development, management and appraisal

- simple circulation systems of resources for all users

- an understanding of intellectual property and copyright issues

- the introduction and integration of digital technologies

- the development, design and delivery of online services

- the establishment of an attractive and supportive library environment

- management of archives and school memorabilia

- the development of clear, identified, safe and fair workflow and work practices

- an understanding of the services and support a qualified teacher librarian can offer

- the professional learning for yourself and your colleagues

- other areas of responsibility specific to your situation

While all areas are important, priorities should be established based on

- your professional knowledge of the needs of the staff and students

- identified in-school priorities so the library’s goals are aligned to those of the school

- external factors such as the implementation of new strands of the Australian Curriculum

- practical concerns such as available or proposed infrastructure

Goals

Goals are concise, specific statements of what will be achieved within a certain time period. They should be SMART.

| S | specific | significant | stretching | sustainable | succinct |

| M | measurable | meaningful | motivational | manageable | |

| A | achievable | agreed | acceptable | action-oriented | authoritative |

| R | relevant | realistic | responsible | rewarding | results-oriented |

| T | timely | tangible | trackable |

To ensure that the goals are achieved, it is necessary to

- allow key stakeholders to have input and ownership

- display them prominently

- identify the starting point, strengths, and weaknesses of each

- identify the obstacles and opportunities that exist

- identify the cost, time and sacrifices or trade-offs that each demands

- develop a plan for achieving each one so the task is manageable

Timeframes

The usual timeframe for a strategic plan is three years as that enables time to identify, implement, expand and review. However, within the overall timeframe, specific smaller periods need to be identified so that the overall plan remains on track. These are based on the identified priorities of what is, what should be and what could be.

Ensure that the timetable for action is published and readily available and establish a communication mechanism so team members are aware of dates and deadlines.

Also create an at-a-glance management plan so progress can be easily seen.

Performance Indicators

Performance indicators are the markers and milestones which demonstrate achievement and ensure that the goals are being met in a timely fashion over the course of the plan. They identify

- how a goal will be measured, either in increments or overall

- what has been achieved

- what needs to be done

- how what has been achieved can be built on

Where possible, identify the benchmark or starting point, and, like the goals, make the performance indicators SMART. While keeping priorities in mind, capitalise on initial enthusiasm and have a cluster at the start of the plan so initial success is achieved quickly, is clearly visible and the foundations for future development are laid.

Set up a public document that clearly shows the progress that is being made so that success can be seen and annotate it to identify the contribution to teaching and learning.

Stakeholders

Because the library belongs to the whole school community and everyone has a part to play, this raises many questions …

- Who should lead the expedition towards achieving the vision?

- Who else should be on the journey?

- Who are the stakeholders?

- What are their vested interests?

- What will they need to know to enable the destination to be reached?

Building your vision with a team offers many advantages including…

- It makes the whole task much more manageable

- It enables a broad range of stakeholders to be involved thus giving them ownership and a greater commitment to ensuring the success of the plan

- It brings a greater range of expertise, experience and viewpoints to the table so best practice is more likely to be achieved

- It enables a greater understanding of what is on offer through the library’s services and why things are done the way they are

- It puts the library at the educational centre of the school for staff, students and parents

- It is a great advocacy tool

Roles and responsibilities

In an address to a conference in Christchurch, New Zealand in 2003, leadership expert Tom Sergiovanni suggested that each team member makes five promises that will help the whole group work together to achieve the vision.

As the teacher librarian, what promises should you make?

Become familiar with the research about the impact of a well-funded, well-resourced school library program under the guidance of a qualified teacher librarian so you know there is well-founded evidence to support your beliefs about your role. Summarise the research into a list of key findings to distribute to team members.

Use the Standards of Professional Excellence for Teacher Librarians to examine your professional knowledge, practice and commitment to identify the areas for personal improvement in relation to achieving the goals of your plan.

Use the descriptions from Learning for the Future, review those roles you have as

- curriculum leader

- information specialist

- information services manager

Identify not only what you do when you wear each hat, but how much time you spend on each.

- Is there a balance or a predominance of one over another?

- What is your key role?

- What are the unique areas of knowledge and expertise that you provide the staff and students as a result of your training that a librarian or administration officer can not?

- What should your priorities be?

- What can you delegate?

Compare the answers to the goals of your plan and identify the priorities that you need to focus on so it can be achieved.

Use what you have learned to develop a personal professional pathway which includes five promises which will enable the achievement of the vision. Use a format such as this…

| Promise | What do I intend to do? |

| Purpose | Why am I doing this?How will it contribute to the achievement of the vision? |

| Strategies | What are the steps that will help me achieve it? |

| Timeframe | When do I plan to start and finish? |

| Support | What do I need – time, people, resources, finance, learning – to achieve this promise? |

| Success | How will I measure and share my success? |

Have each member of the team

- read the research summary

- consider the vision statement and the contribution they can make towards its achievement

- identify the five promises they will make on behalf of the group they represent and how these might be achieved.

- complete a similar document based on their experience, expertise and commitment to the vision.

Publish and display these promises so that everyone in the team in whatever capacity is continually reminded that they are part of a connected community and have a responsibility to it.

Resources

It is essential to identify the resources that will be needed so these can be planned for.

Human – As well as the experience and expertise of the team members, there may be others whose expertise can be co-opted for a particular project. Their availablitiy may influence the priorities of your plan. Human resources may also include obtaining or providing essential professional learning so a target can be achieved successfully.

Finance Many of the components may require financing either within or beyond the library’s normal budget so clear and complete costings are an essential part of the plan so these can be budgeted for by the prinicpal, the teacher librarian or external sources.

Time As the plan’s co-ordinator, the teacher librarian may well need extra time beyond their normal allocated administrative time so this needs to be negotiated with the timeclock holders within the school. Regular team meetings will also need to be held and appropriate times for these need to be negotiated.

Physical Achievement of the vision may require the provision of physical resources such as the reconfiguration of a space or the provision of ICT infrastructure, so these also need to be identified and costed, and their provision worked into the priorities.

External support

Identify the sort of external support that will be required, such as tradesmen to upgrade the ICT infrastructure; experts who can provide appropriate professional learning; collaboration with other staffmembers; or outside funding and integrate these into both the priorities and the budget.

Documentation

Often with a new vision, there is a new focus and direction which brings with it changes or updates of policies and procedures. It is essential that these are done so that the plan can continue regardless of who is sitting in the teacher librarian’s chair.

It is also important for the strategic plan to be formally constructed, published and displayed so that all stakeholders and those in the school community can see that there is purpose supported by identified prioriites and so forth. It also enables progress to be mapped.

As parts of the plan are achieved, document these for future reference, including the pitfalls so there is a clear account of and accounting for all the time and effort that has been expended. Share progress and success with the school community so they are kept informed of the changes and how these are impacting on the teaching and the learning within the school.

Review

A vision and a strategic plan can only ever be guides, not set in concrete. Circumstances change over three years and so there always has to be the flexibility of reviewing the priorities and programs, and changing direction as necessary.

As well, as things are put into place, new opportunities and possibilities open up. But instead of following these detours, perhaps at the expense of your ultimate destination, write them down so they can be new pathways to be explored in your next vision statement. Ensure your steps continue to lead you towards that destination.